On the evening of 5 April 2012, the prime-time bulletin on the television news of the Malawi Broacasting Corporation (MBC), announced to the country that the president, Ngwazi Professor Bingu wa Mutharika, “had…taken ill and had been flown to South Africa for specialist treatment.” At another end of the capital city, Lilongwe, a presidential convoy was on its way to the Kamuzu International Airport (KIA), where an air ambulance awaited with instructions to fly a president who was supposedly alive but unwell to South Africa.

Earlier in the day, around 11:00 in the morning, Ngwazi Bingu had collapsed while receiving in audience the Member of Parliament representing the south-east constituency of the capital city, Lilongwe, Agnes Penemulungu. The judicial commission of inquiry which later investigated what transpired thereafter, received evidence which showed quite clearly that the presidential court had not prepared nor practiced for the possibility of a life-and-death emergency involving the president. Elton Singini, a senior judge, chaired the inquiry.

The commission of inquiry established as a fact that the president died earlier in the day inside the ambulance en route to Kamuzu Central Hospital in the capital city. According to the inquiry report, “the President was brought in dead (BID) at Kamuzu Central Hospital [KCH] at around 11.25 in the morning” of 5 April.

At the time of the news bulletin announcing that he was to be flown to South Africa later on the same day, Bingu had been dead for over eight hours. Despite being aware of this, the presidential retinue instructed staff at the hospital to apply cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on the presidential remains for over two hours. In the process, they crushed his rib-cage.

More was to follow. At the airport, the air ambulance pilots from South Africa declined to board the body, citing the fact that their permission was to fly with a patient not a dead body. High level conversations ensued between Lilongwe and Pretoria. It may have helped and was certainly relevant that Malawi’s Foreign Minister at the time was Peter Mutharika, Bingu’s younger brother who was also intent on stepping into the shoes of his just deceased brother. Peter needed time to set the wheels in motion to leap-frog Vice-President Joyce Banda in the succession stakes.

South Africa’s President, Jacob Zuma, who had retired for the day had to be woken up to personally authorise the flight. Shortly after midnight on 6 April 2012, the air ambulance took off for South Africa. In Malawi, the people were told their president was headed to South Africa for medical attention. In South Africa, the authorities knew that the air ambulance on its way from Lilongwe would arrive with the dead body of Malawi’s president. Shortly after 02:30 a.m. on 6 April, the aircraft landed at South Africa’s National Defence Force (SANDF) Waterkloof Airbase on the outskirts of Pretoria. From there, the dead body was transferred to a mortuary.

The authors of all this malign chicanery designed to deceive the people of Malawi, however forgot to also notify the processes of bio-chemistry. By the time the body arrived the morgue in South Africa, it had been “in the open without refrigeration for about 18 hours after death.” As a result, the very important and high profile invitees to the state funeral of Bingu, which took place on 23 April, 2012, had to endure the uncomfortable company of flies, as well as the majestic fragrance of human putrefaction. As the report of the Elton Singini Commission of Inquiry recorded, “the body had started decomposing as evidenced by the smell and a few flies hovering around.”

Four years earlier, in August 2008, Levy Mwanawasa, the president of neighbouring Zambia, died in a military hospital near Paris in France. While attending the summit of the African Union in Cairo, Egypt, on 29 June 2008, Mwanawasa had collapsed following what was later understood to be an aneurysm (stroke). He was stabilised there before being transferred to France, where he died two months later. At his death, it came out that two years earlier, during his first term as president in 2006, Mwanawasa had suffered an earlier stroke. For that, he received extended treatment in the United Kingdom. No one told Zambians.

The year after the death of Mwanawasa, in June 2009, Omar Bongo, who had ruled Gabon for 41 years, died in a hospital in Spain. When he left Libreville at the beginning of the previous month, his compatriots believed that their president, the doyen and favourite of France Afrique, was away on a working visit – a phrase all too familiar to Nigerians – to his favourite haunts in Europe. At his death, it emerged that more than one month before his death, President Bongo had been hospitalised for cancer treatment in Spain.

President Bongo was not the last long-serving African president to die in Spain. On 8 July 2022, former Angolan president, Jose Eduardo dos Santos, died also there after prolonged cancer treatment. Following his death, a family crisis broke out over his funeral, which delayed the repatriation of his remains to Luanda for more than one month. Six weeks after his death, in the third week of August 2022, a judge in Spain finally authorised the return of the body of dos Santos to Angola for burial.

When he departed Nigeria on 2 April, the presidency in Abuja issued a statement claiming that Bola Tinubu, Nigeria’s president, was off to France on a “short working visit”, during which he would “retreat to review the progress of ongoing reforms and engage in strategic planning ahead of his administration’s second anniversary.” They barely stopped short of telling Nigerians that their president was headed to Lourdes for the grace of its historic apparitions. Tinubu is a Muslim; it was in the middle of the Christian season of Lent and no one had apparently bothered to advise him or his image makers that it is usually Christians who undertake two week-long retreats in the middle of this season.

The day after the end of the initially announced 14 days, the same presidential retinue disclosed that the president had relocated from France to the United Kingdom, from where he was doing an excellent job as Nigeria’s president in Europe.

The evidence seems inescapable that Tinubu has significant health challenges and needs regular medical attention from doctors overseas. For this, his destination of choice is clearly France. In 22 months as president, Tinubu has made at least eight trips to the country under different guises, for a cumulative period of over 60 days.

While he’s been away this time, hundreds – if not more – have been killed in massacres in different parts of Nigeria. As president, Tinubu is also the commander-in-chief of Nigeria’s armed and security forces. Yet, from Europe, he is reported to be passing the buck to state governors to do that which only he has the tools to accomplish under Nigeria’s constitution.

Excluding the five years and three months of the presidency of Goodluck Jonathan, from February 2010 to May 2015, Nigeria has had a presidency in near-permanent occupancy of sanatoriums overseas for 15 years. The Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), which Tinubu led, was aggressively voluble in asking for candour on the health status of a terminally ill President Umaru Yar’Adua. After going into marriage with Muhammadu Buhari’s Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) to create All Progressives Congress (APC), it made a virtue of unlooking when Buhari took up residence in foreign hospitals for much of his presidency.

It should be no news that a man of Tinubu’s age is unwell. Those invested in concealing that reality from Nigerians are more interested in protecting their present perquisites than in the wellbeing of their principal or of the country.

The presidency is more than just an office. For those around the occupant of the office, it also means money, power, and privilege. To preserve it, most people in and around the presidency take liberties, sometimes, even with the wellbeing of their principal or with accountability to the people in whose name he holds office. For the country and even for the president, the wages of this interminable subterfuge are prohibitive.

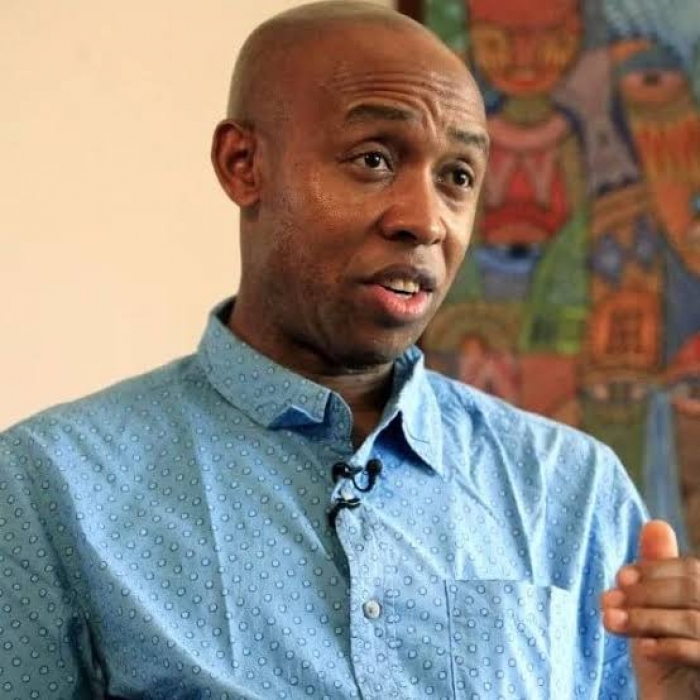

** Chidi Anselm Odinkalu, a professor of law, teaches at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy and can be reached through This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..